Understandably, conversations in the business community have turned to inflation, interest rates and what happens next for the economy. Here we give our view of what’s happening and where it could lead.

The first myth to bust is that the cost of living crisis is being driven by supply issues and events in Ukraine. Inflation is a monetary phenomenon and is driven by the supply of money in the local and global economy. Physical supply issues and the war in Ukraine may mean that inflation is 10% rather than 7-8 %, but it is not the main driver. Current inflationary pressures have been baked into the economy since at least 2016, and were turbocharged by governments turning the taps on again during Covid.

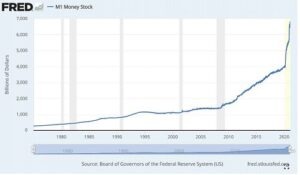

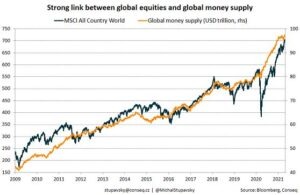

Money supply is driven by interest rates and broader monetary policy. With historically low interest rates and central banks printing money (mainly buying up governments bonds and low risk assets), we’ve had 10 years of extremely loose monetary policy around the globe. That is what is driving inflation and it is easy for all to see.

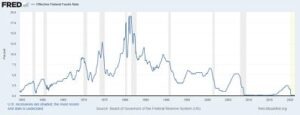

US Interest rates have remained historically low:

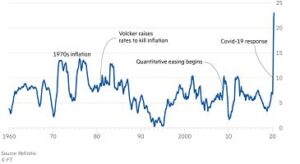

US Fiscal Stimulus hit at an all time high:

The Result has been record growth in US money supply:

It is loose monetary policy that has driven up the supply of money, and that is now causing soaring inflation.

What’s gone wrong?

Inflation is by default a failure of central bank policy. Early indicators of inflation were evident in the US and UK in 2016. The role of the central bank policy makers is to strangle demand BEFORE those inflationary pressures mount up. So why the Failure? In the US, the FED did start raising rates in 2016. This caused a sell off in the stock market. The Trump administration had one overriding economic policy aim – to keep the stock market rising – and successfully lobbied the Fed to rain in its monetary tightening. Indeed, when the stock market sold off in 2016 on the prospect of raising rates, the Fed stepped in and started buying assets, completely negating any impact from the minor interest rate rises.

In the UK it was a similar story for different reasons. Inflationary indicators were there in 2016, yet rather than start raising interest rates, In August 2016, the Bank of England started another round of quantitative easing, buying UK government bonds to address uncertainty over Brexit.

COVID-19 then happened, and governments and central banks abandoned all caution, dropping rates back down and printing as much money as they could. This approach may make sense during a recession, however the shut down of the economy due to COVID-19 was not a recession. This meant governments were pumping money into economies that quickly returned to near full employment as soon as COVID restrictions were eased.

In hindsight it’s clear that central banks should have gone further and faster between 2016 and 2019 to tighten policy and get ahead of the inflationary pressures, but they didn’t. Further loosening of monetary and fiscal policy during Covid has now added fuel to the inflationary fire that was already burning.

Where next?

The US Fed is now clearly on a path of raising rates to choke off demand in the economy. They are likely to go higher and faster than expected, and where the US Fed goes, the Bank of England is sure to follow. The bank of England is going to have to at least match fed rate rises or risk a weakening Pound pushing inflation even higher.

In an ideal scenario, central banks will raise rates quickly and just the right amount to choke off demand before settling into a process of gradually bringing rates back down. The trouble is that leaving this process too late has increased the likelihood that rates will rise too much. It takes 6-9 months for the impact of rates to filter through to the real economy, and central banks can’t wait 9 months to see if it’s working, so they have to go further and harder than they need to just to make sure it works.

Surely energy prices are all about Russia and restricted supply?

There is some view that this bout of inflation is all about energy costs, and that is all about the war in Ukraine restricting supply. If we make sure we increase energy supply, inflation will come back down and no need to tighten monetary policy? This is another myth. As of yet, there haven’t been any real supply restrictions in global energy – there’s plenty oil and gas out there. Oil and gas prices are being driven higher by speculation, and that speculation is driven by the excess money supply. The increase in money supply drives money into riskier assets and we see that in stock markets, commodity and other asset price inflation. The war in Ukraine may have triggered the speculative rise in energy prices, but it is the excess money supply that is fuelling that speculation. Speculation leads to asset price bubbles. This is why leaving it too late to tighten monetary supply risks a far more severe recession. To strangle demand, rate rises will not just need to restrict the amount people can borrow, but will have to burst the speculative bubbles in asset prices, and that causes much more economic pain that just stifling demand early.

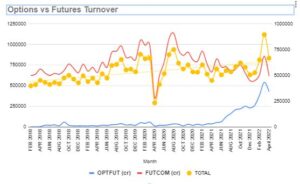

To understand why energy prices are so high you need to understand what is happening in the markets. When Russia invaded Ukraine, every money manager worth his salt poured money into betting that energy prices were going to rise. When everyone piles into a market it becomes self-fulfilling that prices will rise. Speculative money is driving energy costs, The blue line is the one to look at in the below chart – the spike in oil futures volumes driven by speculation. That’s not to say there aren’t potential supply and distribution issues building up, and some countries are more at risk than others, but the price rise is not just supply driven.

To bring energy prices back down, central banks need to burst the speculative bubble. The problem is, to burst the speculative bubble in energy, they need to burst all the money supply driven speculative bubbles. Crypto, stock markets and housing are all showing recent signs of weakness.

Where does this leave us?

Central banks need to strangle demand to get inflation under control, in doing this they will have to also burst the speculative asset price bubbles. Realistically that means we are the point now where a recession is going to happen. The unknown is what governments will do in terms of Fiscal and broader economic policy. In the UK and Wales this is difficult to predict as there is no clear economic policy direction from the government.

The Bank of England is going to raise rates and probably do it faster and go higher than currently expected. They need to strangle demand and reduce the money supply enough to get inflation back to 2%, the only way they can do this is by pushing the economy into recession. The fastest way to reduce demand is to make people unemployed. However, the UK government is unlikely to just do nothing as this happens. The best bet on what the UK government will do is to look at what they’ve just been doing and they think worked. My guess is that at some point the UK government will underwrite bank lending again as it did during covid with CBILS. This might make the recession shallower but could also prolong it by countering the anti-inflationary measures. Another sure thing is that they will also do all they can to support house prices – falling house process lose elections in the UK and they know this. This may mean even mean the government underwriting mortgage lending.

There is one brighter note, the tightening of monetary policy in the early 80s to cut off inflation led to mass unemployment in the UK Those jobs never returned, driven by the winds of globalisation. This phenomenon is unlikely to repeat itself – the trends of globalisation are reversing. The government will have an opportunity to rebuild the economy, short term unemployment should not become structural as it did in the 80’s, and there could even be the opportunity to reindustrialise the economy if the government is smart enough to figure out how.