Much as I’d like to write about something other than inflation, it continues to be the dominant economic concern, so here we go again.

Last month saw a plethora of articles trying to explain why inflation was higher in the UK than in other countries, and none of them gave a wholly satisfactory answer, so I thought I’d look into it.

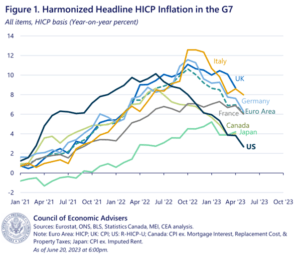

Here’s the comparative inflation chart for G7 countries:

Inflation has broadly followed the same pattern across the G7. That’s important. All counties appear to be on the same inflationary path, which suggests the underlying drivers for inflation are common across all countries. There is not a huge difference in the pattern of inflation, some countries have been above the UK at different points and the numbers and timings may be different, but the underlying trends and patterns are consistent.

The differences can be largely explained by a couple of factors: Energy self-sufficiency, food self-sufficiency, and energy market regulation. Those countries with greater self-sufficiency have seen inflation fall sooner and faster, largely because internal markets tend to be more price efficient – falls in the price of energy filter through more quickly, and food pricing is more efficient as there are no trade barriers. Hence the US saw inflation rise earlier than other countries and fall back sooner.

Therefore, the first conclusion is that talk of differences in inflationary pressures between the UK and other countries is a bit overblown, at least for now.

Why is inflation happening in the first place?

The main reason I question a lot of the current reporting around inflation is because it often misses the point as to what really causes inflation. Central banks and governments have an incentive to peddle a narrative that it’s nothing to do with them, so it’s worth trying to explain how inflation happens (hint – it’s not to do with the Ukraine war and it is to do with central banks and governments).

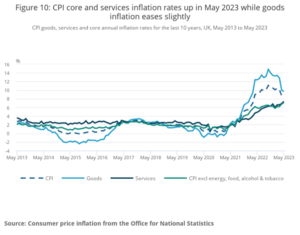

If we look at the inflation chart for the UK split by goods and services, we can see that prices for goods fell during covid lockdowns as demand fell. At the same time, households were building up savings and the government was pumping billions into the economy. As soon as restrictions eased, cash-rich households went on a shopping spree (starting May 2021 – long before the Ukraine war).

The narrative at the time was around supply chains and cost-push inflation and such. Anyone who has studied Economics 101 will be aware of Milton Freeman’s explanation that inflation is always a monetary phenomenon: “Inflation is always and everywhere, a monetary phenomenon. It’s always and everywhere a result of too much money, of a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than of output.”

Inflation is demand-driven, if through loose monetary and fiscal policy you pump too much money into the system, then you will get inflation. The loose monetary and fiscal policies of the last decade were always heading in this direction, inflation just needed a trigger.

The data suggests we are in a good old-fashioned monetary-driven inflation cycle. People had excess money in their pockets, fuelled by years of low-interest rates and government debt, so demand went up. This first shows up in the prices of goods rapidly going up, not because input costs are necessarily increasing or because of supply chains. Businesses put up prices because they can. Excess money in the system moves the price elasticity of demand curve for products. If you had a product you were selling for £100, once demand starts increasing, if you can increase that price to £110 without impacting the number of products you can sell then you do it. This is not “greedflation”, it’s just the way things work and it’s how inflation happens.

This increased demand for goods and increased profits then starts driving commodity demand and prices, driving up input prices, and feeding into full employment. This in turn drives inflation to start filtering through to increased wages and increases in the price of services (where wage costs tend to be a larger proportion of costs), leading to what we see as the “second round” inflationary effects. Goods price inflation tends to ease as inflation starts to throttle the economy, but by this time the secondary effects are already built into the future.

Hence, we are really just in a traditional monetary-driven inflationary cycle driven by too much money pumped into the system.

Central banks might not be saying this but judge them by their actions – even if they are belated – interest rates going up and not yet coming down. They know that inflation is monetary in nature and the only way inflation is likely to go away is through monetary tightening and economic pain. Why central banks were so late to the party is a question that needs to be answered.

Are we now seeing some future divergence between different countries?

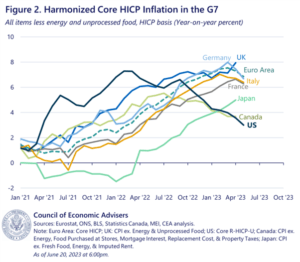

The chart everyone is concerned about when it comes to the UK is this one:

That recent upward spike in core inflation in the UK seems at odds with every other country. While on the face of it concerning, it’s way too early to tell if this is just a timing issue or statistical anomaly in the way things fall in and out of the inflation figures.

Just as much as people are jumping up and down about the UK figures remaining stubbornly high, I suspect they are jumping up and down too much about inflation in other countries appearing to fall. If you look at the US, where on the face of it inflation looks to have come right down, those secondary effect pressures can be seen if you look deeper into the figures. The inflation cycle always appears to follow a double-peaked pattern, there is a lag between the initial goods-driven price rises and then the secondary wage and services-driven wave of inflation, and there is no evidence that the risk of those secondary effects driving a second round of inflationary pressures over the next 12 months has disappeared. I would be very surprised if the Fed starts easing interest rates any time soon.

Are there any differences to the UK economy?

While all countries appear to be in the same inflationary cycle, there are exaggerated risks to the UK. Our dependency on imported goods and commodities, oversized reliance on the service sector, labour market constraints, trade barriers (yes – Brexit), the loosely controlled way in which money was pumped into the economy through furlough and bounce-back loans – all could mean that those secondary round effects are hitting the UK faster and harder than they are hitting other economies, but at the moment it’s a little too early to tell.

Ironically, the country in Europe I would least like to be right now is Spain. Inflation in Spain is around the lowest in the EU at 2%, which you might think is great, but with unemployment at over 12% and interest rates being set by the EU to solve a problem that Spain doesn’t have it means that the Spanish economy is in an extremely precarious position.