The Bank of England (BoE) is currently facing two main challenges – a weak pound and soaring inflation. The only weapon it has to counter both is to raise the interest rate. Gus Williams, the Chief Executive Officer (CEO) at Bevan Buckland LLP, explores the detail surrounding these particular challenges and provides an insight into what you should look out for within the upcoming months.

BoE policy makers have been speaking as much about the weak pound as they have inflation. The weak pound is causing angst for a few reasons. While a weak pound ostensibly helps exports by making UK produced goods cheaper in global markets, the UK’s weakened export position post Brexit and Post Covid means the benefits are negligible. Trade and exports have flatlined since falling significantly during Covid. While most countries have seen trade volumes return to pre-pandemic levels, the UK lost trade which has never returned. Therefore, the negative impacts of a weak pound on a growing trade deficit, as imports become more expensive, is driving inflation higher and at the same time increasing the structural weakness of the UK economy.

The other issue is the UK’s Net International Investment Position, which is the worst of the G7 nations (excluding the US which is an outlier due to the fact the USD is the reserve currency and central banks hold US Govt Bonds in large amounts). The Net international investment position (NIIP) measures the gap between a nation’s ownership of foreign assets and its overseas held liabilities. If you own more overseas assets than you have liabilities, a weak currency increases net overseas income, the opposite is the case in the UK. The UK has long funded its trade and fiscal deficits through foreign inflows – particularly by selling UK government debt abroad. A weakening pound risks driving up Government borrowing costs and this can quickly have a spiralling impact on the UK Balance Sheet.

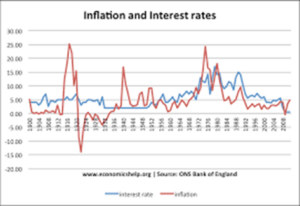

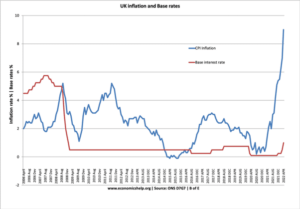

The BoE will feel it needs to get ahead of US interest rate rises to make the pound more attractive to overseas investors. This is on top of the fact that interest rate rises are needed to beat inflation. Traditional monetary doctrine dictates that to beat inflation, interest rates need to rise above the rate of inflation. No one is expecting this to happen. 20 years of low interest rates and low inflation have completely erased the collective memory of this doctrine to the point it is considered ridiculous, but a look at history shows that in fact interest rates above inflation are not uncommon. In the 1930s, before monetary theory was understood, keeping rates well below inflation resulted in the worst boom and bust of the 20th Century and a prolonged economic depression.

What to watch out for?

The Bank of England Monetary Policy Committee meets next on August 4th and then again on September 15th. We will be watching closely to see if they take advantage of the power vacuum in Westminster to raise rates higher and faster than expected. That will give us a better indication of where the economy is likely to head over the next 12 months. The US Fed raised rates 0.75% to 2.5% (Fed raises rates). The ECB raised rates 0.5% to 0% and has signalled further rises. The BoE will almost certainly raise rates 0.5% in August versus an initial consensus of a 0.25% rise. Could they go even further and match the US rate rise? The risk is on the upside.