There will be lots of polarised debate and discussion on the Government’s tax cutting mini budget, that was anything but mini. There will be those who view it favourably, and there will be those who are disgruntled.

We want to take a slightly different approach and simply ask “will it work?” Will the tax cuts achieve their stated aims of driving investment and economic growth?

Reducing taxes is undoubtedly good for individual businesses, giving them more cash. The reduction in NI will relieve some pressure on businesses facing rising wages, and allowing businesses to keep more of their future profits should be positive for business sentiment.

The question is what the economy will as a whole do with that extra cash. If the tax cuts improve business confidence then they could succeed in driving investment and growth, but to counter inflation that investment has to result in improved productivity, and the evidence is mixed.

Do lower taxes increase business investment, productivity and growth?

Economic growth can be achieved in two ways, business investment driving increased productivity, or through increased spending and consumption.

There is no doubt that excessively high taxes dampen business investment. However, this is only really evident when tax rates far exceed comparative global averages. When rates are already roughly in line with other nations, the evidence is less clear – UK rates are around OCED norms.

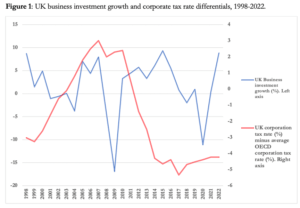

If we look at recent changes in the UK corporate tax rate versus changes in business investment , there is very little positive correlation.

The reason for this lack of correlation is easily explained by the fact that business confidence is the main driver of business investment. Economic certainty increases the likelihood of businesses investing, uncertainty decreases that likelihood. The dips and troughs in business investment above correlate closely to the prevailing economic mood.

When uncertainty is the main driver of business investment decisions, lower corporate tax rates can actually have the effect of reducing investment.

The compelling evidence against tax cuts fuelling investment on their own is that business rates fell from 30% in 2008 to 21% in 2014. Despite these cuts, economic growth and productivity remained below long-term trends.

Businesses make productivity investment decisions on a pre-tax basis. In uncertain times, lowering tax rates too far can encourage businesses to reduce investment and maximise profits, preferring to pay the lower tax rate and build up their cash reserves. After the corporate tax rate fell to 21% in 2014, investment largely flatlined because the prevailing economic driver was the uncertainty of Brexit. Since 2014 many businesses, particularly large businesses, have simply hoarded cash and used those reserves not to invest but to buy back shares. A combination of low interest rates and low corporate tax rates have encouraged this behaviour.

All else being equal, based on the current economic uncertainty, the evidence suggests that the first priority of businesses who benefit from the coming tax cuts will be to pay off debt, maximise profits and build up cash reserves to counter the uncertainty, not invest in productivity and growth.

Recruitment and staffing are a bigger concern for businesses

The real limiting factor to business growth at the moment is recruitment and staffing – we have covered this in a previous blog. This is the second factor in determining whether or not tax cuts will fuel investment. The flip side of businesses struggling to hire, is that businesses need to do all they can to retain current staff. This in turn means that any additional cash businesses receive from the tax cuts is more likely to be passed on to current staff to through pay rises than invested in growth.

Reducing payroll taxes can do little to increase recruitment if there is no one to recruit.

Rising Costs

The final factor to look at is rising costs. Any additional profit from tax cuts that does not make its way to cash reserves or increased pay, will likely be absorbed by rising material costs.

Will the tax cuts increase business confidence and reduce uncertainty?

The above arguments don’t hold if the tax cuts are seen as reducing uncertainty and generate increased business confidence. If the tax cuts fuel some short-term spending and keep GDP growth above 0%, then it is possible that consumer and business confidence will pick up, however this is a very long shot. It is difficult to see how business confidence and certainty will return to positive territory until inflation is tamed and the job market eases up. Neither of these seems likely. The financial markets have spoken with their feet, falls in the stock markets and the £ on the back of the budget suggests markets see increased uncertainty. The main view here is that the tax cuts have increased the risk of further inflation and increased uncertainty around interest rates.

Is the budget inflationary?

Our most likely scenario, that the savings businesses make from tax cuts will mostly filter down to increased wages and costs suggests that increased inflationary pressures are also the most likely outcome from the Government’s tax cuts. In simple terms: With high inflation and a tight labour market, businesses will have to use the cash from tax cuts to fund pay increases to retain experienced staff, feeding inflation rather than investment. The Government will in effect be borrowing to fund inflationary wage increases. This will increase money supply – and inflation is always a monetary phenomenon.

Why has the Government taken these steps?

The historical evidence that tax cuts on their own fuel business investment is limited to non-existent. There is, however, better evidence that tax cuts can fuel spending and consumption.

The Government seems to be betting that reducing NI and Income tax rates will fuel additional consumption, and that this combined with maintaining low corporate tax rates will fuel business investment and growth.

While the above sounds reasonable in theory, economic orthodoxy throws a couple of spanners in the works. With price inflation outstripping wage growth, even with the tax cuts, relative incomes are falling. To increase consumption, taxes would need to fall at such a rate as to increase incomes at a faster rate than inflation while driving huge productivity increases in supply to counter the demand. These cuts do not do anything to achieve that scenario. Relatively minor tax cuts for the majority of workers will quickly become consumed by inflation and will be unlikely to increase overall consumption.

So this still leaves the question, given the evidence, why has the government cut taxes? Firstly, as the Government itself admits, it’s a gamble that the evidence and orthodoxy are wrong. There is also undoubtedly a genuine ideological belief amongst some that simply cutting taxes always leads to growth.

A more cynical view would be that the Government knows that its chances of winning the next election are rapidly diminishing, and that despite the huge gamble, it is worth the risk. They have nothing to lose. If it works, all is good, if it doesn’t work, an incoming Labour government would be left with an economic mess and would have to immediately raise taxes, fitting the Conservative narrative.

What else does history teach us?

These are the biggest tax cuts since 1972. Those tax cuts were the starting point to a chain of events that ultimately lead to the inflation, stagflation and recessions of the 1970’s and early 80s. The results of other large tax cutting budgets in the past are more mixed. The rule of thumb here is that post-recession tax cuts, especially when unemployment is high, inflation is low, and interest rates are falling, can lead to increased consumption driven growth, at least in the short term. This is most evident when there is excess capacity in production. None of these circumstances currently apply. Tax cuts when the labour market is tight (in 1972 there was still full employment) and interest rates are rising tend to be inflationary.

The housing market

One final thought. I have stated here before that whatever happens, the Conservative government was almost certain to do everything it could to prop up the property market. A golden truth in political circles in the UK is that rising house prices win elections and falling house prices lose elections. The rise in the Stamp Duty threshold in England is no great surprise – the subsequent jump in mortgage rates will have terrified the government.